When bringing a child onto an adult ICU, it’s likely that both the child and ICU staff might have some trepidation. It is extremely important to include hospital staff in the plan for bringing a child to bedside. Inclusion of bedside nurses, charge nurse, and social services allow for open communication as well as time to address any concerns staff might have about bringing a child onto the unit. It is the hope that this approach of working cohesively with the hospital team will ultimately make the outcome more comfortable for all parties involved.

Step One: Present the situation for staff members who will be affected by the child’s visit.

This pertains not only to your bedside nurse, but others on the unit. The charge nurse is a key player in the visit, as they can help facilitate any special needs you might have. Present a clear picture as to who will be coming on the unit, the reason for the visit, and an estimation of how long the visit is planned for. It is helpful to let hospital staff know that you are working with the family’s wishes to facilitate an appropriate goodbye for the child.

Step Two: Once you have presented your plan for the visit it is important to acknowledge any concerns that hospital staff might have.

Listen carefully to concerns and address them. The culture and environment of each hospital will vary. Some adult ICUs do not allow children under 12 to participate in visitation. As a result, it is likely that some staff involved will be uncomfortable with the idea of a child coming to bedside. Take the time to acknowledge what they are saying; they might raise a point that will alter your plan.

Step Three: If concerns do arise, support those who are having difficulty with the plan.

Some concerns may be due to timing (change of shift, assessments, etc.) which we can work around. Other concerns may come from minimal experience of working with children who are grieving or simply the uncomfortable nature of seeing a child in emotional pain. Rely on institutional wisdom and what we know to be true about children and grief, and share what you know in a manner that is respectful.

Step Four: Take some time to really survey the scene.

The ICU environment is an extremely foreign place for children. Be creative in finding ways to minimize the stress of the experience. Here are some things to consider while doing your survey…

The ICU environment is an extremely foreign place for children. Be creative in finding ways to minimize the stress of the experience. Here are some things to consider while doing your survey…

- Walk the path of the child (is there another more direct route?); if the child is small, get down low and take in that perspective (you might be surprised at how you feel).

- Is it possible to draw curtains or shut other patient’s doors?

- What is the bedside environment like; think of the senses (is it bright, is there a smell, what is the noise level) and are there ways to minimize these things?

- Work towards presenting the patient’s physical appearance to the child in the most appropriate manner.

- Where is the best place for the child to stand, sit, etc.?

Once your survey is complete you may have requests or require assistance from hospital staff. Never assume that it is okay to execute your requests without consulting with hospital staff; for example, drawing curtains or shutting doors. Again, go back to step one. Hopefully the groundwork you have laid with the hospital staff from earlier will make the facilitation of your needs a much smoother process.

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.

The personal qualities of those who choose to work in the OPO field—including empathy and dedication—combine with the unpredictable and demanding nature of the work itself to create a perfect storm. Your work can become your life and donor families can become “your” families.

When professionals don’t set appropriate boundaries, potential donor families underestimate their own coping skills and can become dependent. Families who help each other feel empowered, and this is very important to their recovery from acute grief. When they see us give too much, some family members will turn their energies to helping the helpers… clearly not in their best interests. When your relationship with them ends, as it must, this can constitute another loss. Setting professional boundaries can help them avoid this loss. Remember, we represent the worst time of their lives; encouraging families to move beyond those memories and any reliance on us contributes to their healing.

You are touched and changed by your experiences with families. Honoring your contact with them will help to give you closure and allow you to move forward. Take time to think about the deep human connection that often occurs; acknowledge it as an important part of your life as well as the family’s. Consider keeping a small memory book where you can enter the names of the people you’ve worked with, your hopes and wishes for them. And then turn the page, so that you’re ready for the next family. Make time with colleagues to talk about the human dimensions of your cases; consider creating a memorial to families at the office. In presentations, briefly acknowledge the courage and generosity of families, so that they are never only donation cases.

Finally, you must learn how to build your personal resilience. Identify strategies to deal with stressful events in the moment, including relaxation, stepping away, and seeking support. And perhaps, even more importantly, dedicate time and attention to your own well-being: exercise, healthy nutrition, time with family and friends. Put yourself on your own calendar!

Finally, you must learn how to build your personal resilience. Identify strategies to deal with stressful events in the moment, including relaxation, stepping away, and seeking support. And perhaps, even more importantly, dedicate time and attention to your own well-being: exercise, healthy nutrition, time with family and friends. Put yourself on your own calendar!

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.

At times of tragedy, parents and many professionals feel a strong impulse to protect children from what is happening. Usually, families are thinking about this decision for the first time, so it is valuable to share some of the following information about children’s grief. However, it is important not to expose children to experiences that they may be too young to understand and these recommendations will not apply to most children under the age of four years.

- Children are typically very clear about their preferences; when they wish to say goodbye, with appropriate support, it is a constructive experience. Equally, a child who expresses reluctance should not be pressured.

- Being left out can leave children with a lifetime of regret and recriminations, especially if the child has expressed a wish to be present.

- Children’s fantasies about what they are not permitted to see are often much more gruesome and frightening than the reality.

- Preparation allows the child to voice questions and fears and have them answered.

SUGGESTIONS FOR PREPARING A CHILD TO SAY GOODBYE

STEP ONE

Share information with the parents about the benefits of inclusion for children and describe the recommendations for preparing children. Offer your assistance but remember it is the parent’s decision to make. If parents do not wish to include their child, respectfully ask if there is any other way you can help.

STEP TWO

If parents accept your assistance:

- Sit with the child and his/her parent(s) and explain the option to say goodbye in age-appropriate language. Assure the child that the doctors and nurses have done everything they can, but haven’t been able to make their loved one better.

- Talk about the grown-ups being sad and upset… ask if that is hard.

- Ask the child whether s/he would like to say goodbye; say that you and their parent(s) will be with them and that they can leave as soon as they would like to.

- Use the “Some children…” technique to ascertain how they are feeling. (“Some children worry that it would be scary… what do you think?”)

- If the child chooses to say goodbye, use age appropriate language and describe the room, equipment, smells, noises, and (most important) what their loved one will look like.

- Check back with the child: “Now I have told you all about it, would you still like to say goodbye?”

- Some children change their minds at this point. If this happens, reassure them that it is good that they are making their own decision and offer the options of drawing a picture or sending a message to their loved one.

STEP THREE

When children say “yes”:

- Together with the parent(s) accompany the child into the room. It is important not to displace the parent(s) at this sensitive time. Additionally, it can be very helpful to parent(s) to hear how you talk with their child about painful topics.

- Point out to the child the things that you described (see STEP TWO, FIFTH BULLET). Go through all the senses (what do they see? hear? smell? etc.). Ask what else they are noticing and whether they have questions.

- Encourage them to talk to their loved one, to touch him or her as appropriate, and say goodbye.

- Again ask if there are any more questions.

Essential final steps:

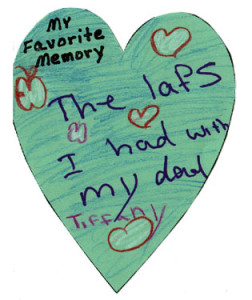

- Sit down with child and parent and ask whether you did a good enough job of explaining everything. Did you leave anything out? Was anything worse than expected?

- RESTORE THE LIVING MEMORY: Ask the child to tell you about a time they had fun with their loved one. Ask about ordinary details (but try to go through all the senses to reinforce the memory): What did they do? What did they eat? What was the weather like? What did it sound like? Smell like? Look like? (all the colors) Did they laugh a lot together? Say how wonderful it sounds and that you understand how much they will miss their loved one “but you will always keep them and these memories in your heart.”

- To reinforce this message with younger children, make gathering motions with your hands (as though capturing memories) and pretend to put them in your heart.

- Check with the parent(s) whether they have questions and ensure that they are comfortable with what has happened.

Most children welcome the opportunity to say goodbye to a loved one and, when thoughtfully planned and carried out, this can be a strengthening and healing experience. Just remember, that although we have learned from research and experience that most children benefit from inclusion, it is important to acknowledge that the loss of a loved one is outside a child’s normal range of experience.

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.

Typical concepts of death and grief responses for the major developmental stages of children are outlined below. It is important to note that there may be overlap between the age groups.

Infancy to Age 2

Concept of Death: This age group typically does not understand the meaning of death, but infants have awareness of loss and separation. They react more to the emotional reactions of adults in their environment and to any disruptions in their schedule.

Grief Response: Babies may search for the deceased and become anxious as a result of the separation. Common reactions include: protest, a change in sleep habits, decreased activity and weight loss.

Preschool (Age 2-4)

Concept of Death: For this age group, death is seen as temporary and reversible. Preschoolers usually do not visualize death as separate from life and don’t see death as something that happens to them. Typical comments include: “When will my mommy be home?” “How does (the deceased) eat or breathe?”

Grief Response: Typically this group’s emotional response is brief but intense, as they tend to be present-oriented. Preschoolers are more concerned about altered patterns of care or about the emotional reactions of adults in their lives. Other typical responses include: confusion, night-time agitation, frightening dreams and regressive behaviors, such as bedwetting.

Early Childhood (Age 4-7)

Concept of Death: This group still views death as reversible. Children sometimes feel responsible for the death because of thoughts or feelings that they’ve had about the deceased, sometimes called “magical thinking.” “It’s my fault. I was mad at her, and I wished she’d die.”

Grief Response: Repetitive questioning about the death process is typical of this age group. “How?” “Why?” They may play act the death or the funeral as an attempt to work through their grief. They may behave as if nothing happened. Other typical responses include: anger, sadness, confusion, difficulty eating, sleeping or regressive behaviors, such as bedwetting.

Middle Years (Age 7-11)

Concept of Death: This age group may want to see death as reversible but they begin to see it as something final. They still don’t think of death as something that can happen to them or their family members, but instead to old people or very sick people. They may believe that they can escape from death through their own efforts. They also might view death as a punishment (particularly before age nine). Children in this age group may develop fears of bodily harm and mutilation, and may fear that other loved ones will die.

Grief Response: This age group typically wants to know very specific details about the death. They may become concerned with how others are responding to the death. They may act out their anger and sadness and may have trouble progressing in school. They also may have a jocular attitude about the death, or may withdraw and hide their feelings. Children at this age sometimes become overly concerned about their own health. Other typical responses include: shock, denial, sadness and regression.

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.