The Institute’s latest eLearning course – “Reaching Across Cultures” – equips learners with essential skills to navigate cultural nuances when it comes to organ and tissue donation among diverse populations. The content was developed by Dr. Heather Marie Gardiner, professor of social and behavioral sciences at Temple University’s College of Public Health. Gardiner recently joined Instructional Designer Shimrit Lee to discuss her research and the importance of education in fostering a more inclusive and effective donor community.

Shimrit Lee: Tell us about your research.

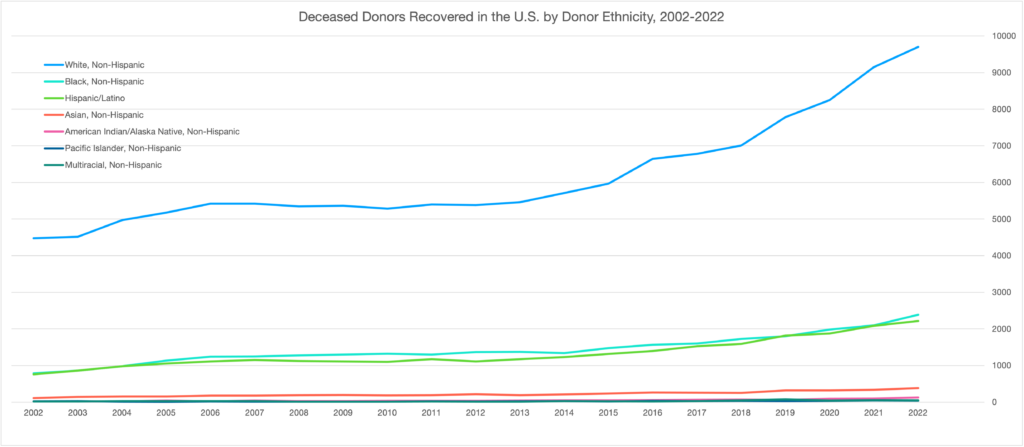

Heather Marie Gardiner: My work focuses on addressing health disparities, particularly in the realm of organ and tissue donation and transplantation. At the Health Disparities Research Lab, my team and I are dedicated to improving the organ donation process, reducing transplant inequities, and increasing access to transplantation services for marginalized communities.

SL: What kind of methods do you use to track disparities?

HMG: I employ a mixed-methods approach, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. This includes developing and implementing protocols for in-depth interviews and focus groups and employing structured and semi-structured surveys. Additionally, I apply advanced statistical methods to analyze data and uncover patterns and disparities in health outcomes related to organ donation and transplantation.

One of the core aspects of my research is community engagement. At the Lab, we actively involve underserved minority populations in our research initiatives to ensure that our work directly addresses their needs and challenges. This community-centered approach not only informs our research design and implementation but also enhances the impact and relevance of our findings.

SL: What do you see as the most significant barrier to transplantation for marginalized communities?

HMG: First, I just want to emphasize that no population is a monolith. Plus, it’s nearly impossible to identify a single barrier to donation. Among African Americans, for example, disparities in donation are rooted in a complex interplay of historical mistrust of the medical system, concerns about fairness in organ allocation, and cultural and religious beliefs.

To overcome these barriers, targeted efforts are required to address misconceptions, improve education about the organ donation process, and rebuild trust within the healthcare system. Community engagement, culturally sensitive outreach, and collaboration with religious leaders can play pivotal roles in fostering a greater understanding and acceptance of organ donation among this group. Efforts must focus on promoting transparency, equity, and inclusivity within the donation system to encourage broader participation and ultimately save more lives.

SL: What is the role of education in reducing these barriers?

HMG: Training in culturally humility is integral to ensuring organ donation professionals understand diverse perspectives and engage in respectful and effective communication. This involves dispelling myths, addressing concerns related to religious or cultural beliefs, and being aware of how implicit biases may affect interactions with patients and families. Training in trauma-informed approaches is also key to understanding the emotional and psychological aspects of donation conversations. These are all topics covered in the eLearning course that the Institute is offering.

Education efforts should align with policy changes aimed at reducing disparities in donation opportunities. This includes advocating for equitable access to donation services and addressing systemic barriers that disproportionately affect certain communities.

Lara Moretti has been providing bereavement counseling and support for families of organ and tissue donors since 2003 at Gift of Life Donor Program (GLDP). Currently the Director of Family Support Services at GLDP, Lara has served as secretary and co-chair of the AOPO Donor Family Services Council. She is also a member of the Gift of Life Institute’s faculty, where she leads trainings on the impact of loss and grief on family donation conversations. Lara was recently a named a Fellow in Thanatology: Death, Dying and Bereavement from the Association for Death Education and Counseling for demonstrating knowledge, experience, and education in death, dying, and bereavement.

We sat down with her to learn more about thanatology and its application to her work at Gift of Life.

What is thanatology?

Thanatology is the study of death, dying, and bereavement and the impact death has on those who are grieving.

What prompted you to study it?

As a bereavement counselor for donor families, I wanted to increase my knowledge about grief so I could better support the families we serve.

What have you learned about grief through your fellowship that surprised you?

I have been surprised by how resilient families are. Even though they have experienced a major loss, they show grace and compassion and can grow from the trauma they endured. Also, I have a greater appreciation for grief after non-death losses, such as the loss of one’s health, job, or home.

You work in family support services. How has your study of thanatology impacted your work in supporting donor families and recipients as well as the information you share through the Institute?

I feel I have a more well-rounded understanding of grief and that has allowed me to support families and recipients in their different displays of grief. Helping grieving individuals understand that what they are experiencing is normal can hopefully alleviate some of the pressure they put on themselves to grieve in the “right way.” There is no one right way. There is only your way.

In my work with the Institute, I see how critical it is to train donation professionals about acute grief so they can be better prepared to support families in conversations about donation. Most health care professionals have no formal training on grief so we enter the field with our own perceptions and ideas about what grief should look like.

What do you wish more people understood about grief?

In general, I think we are a fairly grief illiterate society even though all of us will experience grief in our lives. I wished more people understood that grief can manifest itself in not just emotional reactions but also spiritual, physiological, and cognitive reactions as well. Additionally, grief is not something that needs to be fixed or cured. It is a long process that must be experienced after a loss.