Grief & Bereavement

As donation professionals, we can help our families to identify and recognize the losses they have experienced during the past year, and we can validate them. We can also help donor families “name and claim” the grief that goes along with these losses. Giving voice and validation to what they are experiencing can be a way to enfranchise their grief and make it real. We can encourage families to find meaning in the losses; hopefully we are all able to connect with friends and family more this season than last, but remember how much our donor families may be carrying, and let them know we care.

Acknowledge the loss

Acknowledge the loss

This may seem obvious but it’s okay to acknowledge that the holidays will be difficult without the person who has died. It’s likely that friends and family members will avoid talk of the holidays or mentioning the loss. And for the grieving individual, that avoidance can feel hurtful and isolating. Say something. Normalize their experience. “This time of year could be really hard without having your husband around.” That simple sentence will open the door to a deeper conversation about the person who died and his or her family.

Ask about past holidays

During the authorization conversation, you’re likely going to ask the family to tell you about the potential donor. Ask them about how they celebrated the holidays last year. Or ask them if the potential donor had a special tradition or favorite holiday ritual. This will allow you to learn more about the family and their loved one and it will allow the family to reminisce and recollect, both important parts of mourning.

Support their plans

Some grieving families will share with you that that they plan to skip the holidays completely this year. Others will decide they need to recreate their loved one’s special holiday routines or traditions. Both are normal and totally acceptable. When a grieving family member shares their ideas for what they will do for the holidays, don’t pass judgment. Just let them talk.

Don’t wish them a “Happy Holiday”

Again, this might seem obvious but phrases like “Happy Holidays” come out of our mouths so easily during December. Be especially aware not to finish a conversation with this. Instead, you can wish them peace and comfort. You can tell them you hope they will be surrounded by people who love and care for them. Don’t just convey this with words. Pay special attention to your non-verbal communication. Eye contact, tone of voice and nodding your head all suggest your genuine holiday wish for them.

Give them a gift

Of course we don’t mean a gift you buy at a store. We mean the gifts of compassion, the opportunity of donation and a listening ear. We are often the one person who walks into their room of sadness and crisis while everyone is walking out. Bearing witness to their pain, allowing them to express their feelings and just being present is a gift.

A poem by Nancy Myerholtz hangs in our office so we never forget that we can give donor families “The Gift of Someone Who Listens.” Following is an excerpt:

It wasn’t the person with answers

Who told us of ways to deal,

It wasn’t the one who talked and talked

That helped us start to heal.

We need to always remember

That more than words we speak,

It’s the gift of someone who listens

That most of us desperately seek.

So as we get closer to the end of the year, don’t forget that for the families we interact with, this will be a December like none other. They may not remember your name but they will remember how you made them feel during the donation process. This is true all year round but around the holidays, everything is magnified. And for those of you who are working on the holidays instead of spending it with your family, thank you for your commitment to providing our donor families with the support and compassion they deserve.

Lara Moretti, LSW, FT is the Director of Family Support Services at Gift of Life Donor Program in Philadelphia, PA; Emily Jauregui, LPC, CT is a Family Support Counselor at Gift of Life Donor Program in Philadelphia, PA

As we recognize International Overdose Awareness Day (August 31) and National Recovery Month (September), it is important to remember that how a person dies does not define the person’s life or character, nor does it diminish the suffering experienced by those left behind. Despite increased awareness of its widespread impact, both mental illness and addiction remain stigmatized throughout our society. As a result, grief associated with losing a loved one may be compounded when death ensues as a result of addiction.

Addiction is comprised of an entire series of losses that begin before the death. Often, the losses start when the individual first succumbs to substance abuse. Friends and family watch helplessly as the person they know and love transitions into someone completely unfamiliar. New undesirable behaviors, interests, and people enter into focus. Plans and expectations for the future no longer seem feasible. Trust may be challenged and likely broken. The dynamics of the relationship change or dissolve completely. Although the person in the throes of addiction is still physically present, friends and family may find themselves mourning the person they once were. It may feel strange to grieve someone who is still alive, but the associated emotions are real and valid. This common, yet confusing, experience has a name – ambiguous loss.

Family and friends often feel powerless when their loved one is under the control of addiction. They begin to prepare themselves and accept that this may invariably end poorly. Each of their loved one’s absences from a social gathering is a reminder of their potential void. Every time the phone rings, friends and family flinch and wonder if this is “the call”. The process of expecting the loss of a loved one is known as anticipatory grief. Many of the emotions of anticipatory grief (e.g., sadness, anxiousness, anger, regret) are the same feelings one may experience after a loss. Watching someone suffer through the illness of addiction while adjusting to the reality of losing them is exhausting. Often there is a sense of relief when the death actually occurs. Although this relief may seem wrong and may trigger feelings of guilt, this experience is quite common. It’s important to remember that this relief does not minimize the love for the person who died.

Surviving loved ones often feel as though their loss and grief is disenfranchised. Disenfranchised loss may arise when the circumstances of the death are stigmatized or possess negative connotations. Survivors may feel like they don’t have the right to grieve because society’s message is that their loved one’s death was preventable, shameful, or their own fault. They may feel as though they cannot openly mourn due to the constraints of “societal rules’ and keep their grief hidden. They may feel embarrassed or ashamed as they internalize cultural beliefs around addiction. But it is imperative to remember that no one has the authority to dictate who, how, what, when, or why we grieve. And as we recognize National Recovery Month, it is also important to remember that addiction is not a choice, it is a disease.

Jacqui Kates, LCSW, CT is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in Pennsylvania, a Certified Thanatologist (expertise in death, dying and bereavement), and former Family Support Services Counselor at Gift of Life Donor Program.

When bringing a child onto an adult ICU, it’s likely that both the child and ICU staff might have some trepidation. It is extremely important to include hospital staff in the plan for bringing a child to bedside. Inclusion of bedside nurses, charge nurse, and social services allow for open communication as well as time to address any concerns staff might have about bringing a child onto the unit. It is the hope that this approach of working cohesively with the hospital team will ultimately make the outcome more comfortable for all parties involved.

Step One: Present the situation for staff members who will be affected by the child’s visit.

This pertains not only to your bedside nurse, but others on the unit. The charge nurse is a key player in the visit, as they can help facilitate any special needs you might have. Present a clear picture as to who will be coming on the unit, the reason for the visit, and an estimation of how long the visit is planned for. It is helpful to let hospital staff know that you are working with the family’s wishes to facilitate an appropriate goodbye for the child.

Step Two: Once you have presented your plan for the visit it is important to acknowledge any concerns that hospital staff might have.

Listen carefully to concerns and address them. The culture and environment of each hospital will vary. Some adult ICUs do not allow children under 12 to participate in visitation. As a result, it is likely that some staff involved will be uncomfortable with the idea of a child coming to bedside. Take the time to acknowledge what they are saying; they might raise a point that will alter your plan.

Step Three: If concerns do arise, support those who are having difficulty with the plan.

Some concerns may be due to timing (change of shift, assessments, etc.) which we can work around. Other concerns may come from minimal experience of working with children who are grieving or simply the uncomfortable nature of seeing a child in emotional pain. Rely on institutional wisdom and what we know to be true about children and grief, and share what you know in a manner that is respectful.

Step Four: Take some time to really survey the scene.

The ICU environment is an extremely foreign place for children. Be creative in finding ways to minimize the stress of the experience. Here are some things to consider while doing your survey…

The ICU environment is an extremely foreign place for children. Be creative in finding ways to minimize the stress of the experience. Here are some things to consider while doing your survey…

- Walk the path of the child (is there another more direct route?); if the child is small, get down low and take in that perspective (you might be surprised at how you feel).

- Is it possible to draw curtains or shut other patient’s doors?

- What is the bedside environment like; think of the senses (is it bright, is there a smell, what is the noise level) and are there ways to minimize these things?

- Work towards presenting the patient’s physical appearance to the child in the most appropriate manner.

- Where is the best place for the child to stand, sit, etc.?

Once your survey is complete you may have requests or require assistance from hospital staff. Never assume that it is okay to execute your requests without consulting with hospital staff; for example, drawing curtains or shutting doors. Again, go back to step one. Hopefully the groundwork you have laid with the hospital staff from earlier will make the facilitation of your needs a much smoother process.

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.

Lara Moretti has been providing bereavement counseling and support for families of organ and tissue donors since 2003 at Gift of Life Donor Program (GLDP). Currently the Director of Family Support Services at GLDP, Lara has served as secretary and co-chair of the AOPO Donor Family Services Council. She is also a member of the Gift of Life Institute’s faculty, where she leads trainings on the impact of loss and grief on family donation conversations. Lara was recently a named a Fellow in Thanatology: Death, Dying and Bereavement from the Association for Death Education and Counseling for demonstrating knowledge, experience, and education in death, dying, and bereavement.

We sat down with her to learn more about thanatology and its application to her work at Gift of Life.

What is thanatology?

Thanatology is the study of death, dying, and bereavement and the impact death has on those who are grieving.

What prompted you to study it?

As a bereavement counselor for donor families, I wanted to increase my knowledge about grief so I could better support the families we serve.

What have you learned about grief through your fellowship that surprised you?

I have been surprised by how resilient families are. Even though they have experienced a major loss, they show grace and compassion and can grow from the trauma they endured. Also, I have a greater appreciation for grief after non-death losses, such as the loss of one’s health, job, or home.

You work in family support services. How has your study of thanatology impacted your work in supporting donor families and recipients as well as the information you share through the Institute?

I feel I have a more well-rounded understanding of grief and that has allowed me to support families and recipients in their different displays of grief. Helping grieving individuals understand that what they are experiencing is normal can hopefully alleviate some of the pressure they put on themselves to grieve in the “right way.” There is no one right way. There is only your way.

In my work with the Institute, I see how critical it is to train donation professionals about acute grief so they can be better prepared to support families in conversations about donation. Most health care professionals have no formal training on grief so we enter the field with our own perceptions and ideas about what grief should look like.

What do you wish more people understood about grief?

In general, I think we are a fairly grief illiterate society even though all of us will experience grief in our lives. I wished more people understood that grief can manifest itself in not just emotional reactions but also spiritual, physiological, and cognitive reactions as well. Additionally, grief is not something that needs to be fixed or cured. It is a long process that must be experienced after a loss.

As healthcare professionals, we are taught how to deal with the medical, surgical, and immunological aspects of organ donation and transplantation. But we are rarely taught and often not prepared to deal with the unique emotional, social, and spiritual needs of potential donor families. However, as donation professionals, we have a responsibility of ensuring compassionate care during the painful journeys of these families and how to successfully companion them.

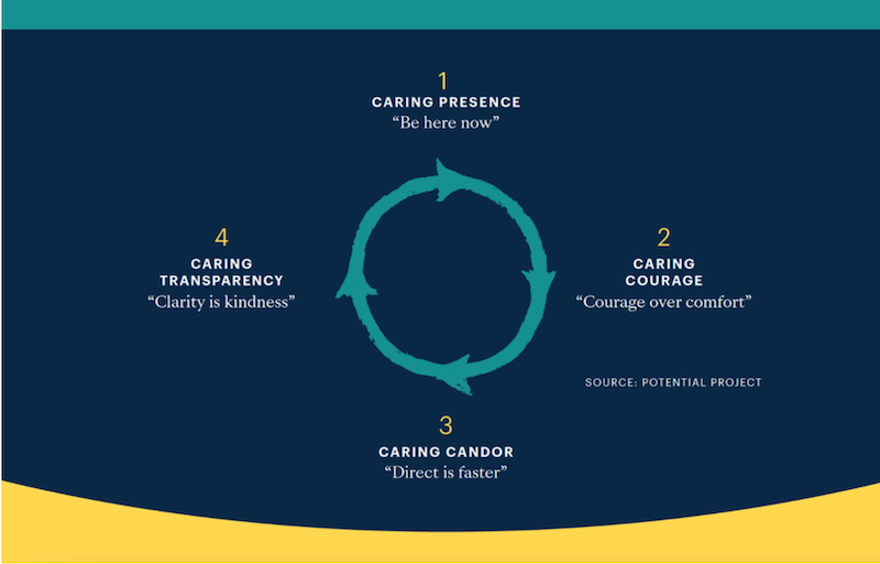

In an article entitled “How to be Compassionate” by Rasmus Houggaard (a meditation and mindfulness expert who has studied with the Dali Lama and current CEO of Potential Project, which helps organizations to build more human and compassionate workplaces), the author and his colleagues looked at what compassion looks like in action and what skills one needs to develop it. They identified four skills as paramount: Presence, Courage, Candor, and Transparency.

Following is an excerpt provided by the app “Ten Percent Happier” that summarizes these four skills.

Caring Presence: Be Here Now

When we are present, we are in the moment and giving the people around us our full attention. Unfortunately this is not our default state. We are wired to be distracted. Mindfulness allows us to be present with others to tie in to what they are experiencing and may not be saying. This helps us to remember that the person in front of us deserves our respect, attention, care and curiosity.

Caring Courage: Courage over Comfort

Once we are present, we can choose courage over comfort. As human beings we are hardwired to embrace certainty and safety to avoid danger and discomfort. Compassion requires us to open up to others. It takes courage to tap into the difficult feelings we and they may be feeling. We find the inner strength to overcome being outside our comfort zone and open ourselves to emotions – ours and others to allow a connection to begin

Caring Candor: Direct is Faster

Having checked in with yourself and the other person the third step is caring candor. This means being direct and straightforward which is the fastest way to engage in a conversation. Caring candor allows you to deliver the message in the most kind and direct way which allows the other person to receive it quickly and for the real conversation to begin. It means being direct and decisive while remaining authentically open to other people’s perspectives and demonstrating care for their emotions and well being.

Caring Transparency: Clarity is Kindness

Caring transparency means getting ideas and thoughts out into the open; to make the invisible visible. When you are transparent, people know what is on your mind. When we start the journey towards greater compassion, we are present in our interactions with others and have the courage to show up with candor and transparency. When we present ourselves in this way it allows others to do the same.

Supporting and accompanying our donor families during the raw and tender time of donation is one of the most important responsibilities of the donation professional. It is also one of the deepest privileges.

The personal qualities of those who choose to work in the OPO field—including empathy and dedication—combine with the unpredictable and demanding nature of the work itself to create a perfect storm. Your work can become your life and donor families can become “your” families.

When professionals don’t set appropriate boundaries, potential donor families underestimate their own coping skills and can become dependent. Families who help each other feel empowered, and this is very important to their recovery from acute grief. When they see us give too much, some family members will turn their energies to helping the helpers… clearly not in their best interests. When your relationship with them ends, as it must, this can constitute another loss. Setting professional boundaries can help them avoid this loss. Remember, we represent the worst time of their lives; encouraging families to move beyond those memories and any reliance on us contributes to their healing.

You are touched and changed by your experiences with families. Honoring your contact with them will help to give you closure and allow you to move forward. Take time to think about the deep human connection that often occurs; acknowledge it as an important part of your life as well as the family’s. Consider keeping a small memory book where you can enter the names of the people you’ve worked with, your hopes and wishes for them. And then turn the page, so that you’re ready for the next family. Make time with colleagues to talk about the human dimensions of your cases; consider creating a memorial to families at the office. In presentations, briefly acknowledge the courage and generosity of families, so that they are never only donation cases.

Finally, you must learn how to build your personal resilience. Identify strategies to deal with stressful events in the moment, including relaxation, stepping away, and seeking support. And perhaps, even more importantly, dedicate time and attention to your own well-being: exercise, healthy nutrition, time with family and friends. Put yourself on your own calendar!

Finally, you must learn how to build your personal resilience. Identify strategies to deal with stressful events in the moment, including relaxation, stepping away, and seeking support. And perhaps, even more importantly, dedicate time and attention to your own well-being: exercise, healthy nutrition, time with family and friends. Put yourself on your own calendar!

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.